In their academic article “Anxious Immobilities: An Ethnography of Coping with Contagion (Covid-19) in Macau,” international tourism scholar Dennis Zuev and business scholar Kevin Hannam outline life under lockdown from the perspective of mobility, through a series of ethnographic studies. Macau is a Chinese city that enjoys the status of special administrative region due to its Portuguese colonial history, meaning it elects its government and formulates its own policies. Cross-border movement is integral to life in Macau as its prosperous casino industry attracts droves of tourists from mainland China, and locals may choose to live in neighboring Chinese cities while traveling to Macau for work every day. The authors coined the term “anxious immobilities” to describe the lockdown experience in Macau, “a total disruption of everyday rhythms and specifically [anxiously] waiting for the normalization of activity while being the subject of biosocial narratives of quarantine and social responsibility of remaining immobile” (Zuev and Hannam 36), referring to a restriction of movement that is seemingly indefinite.

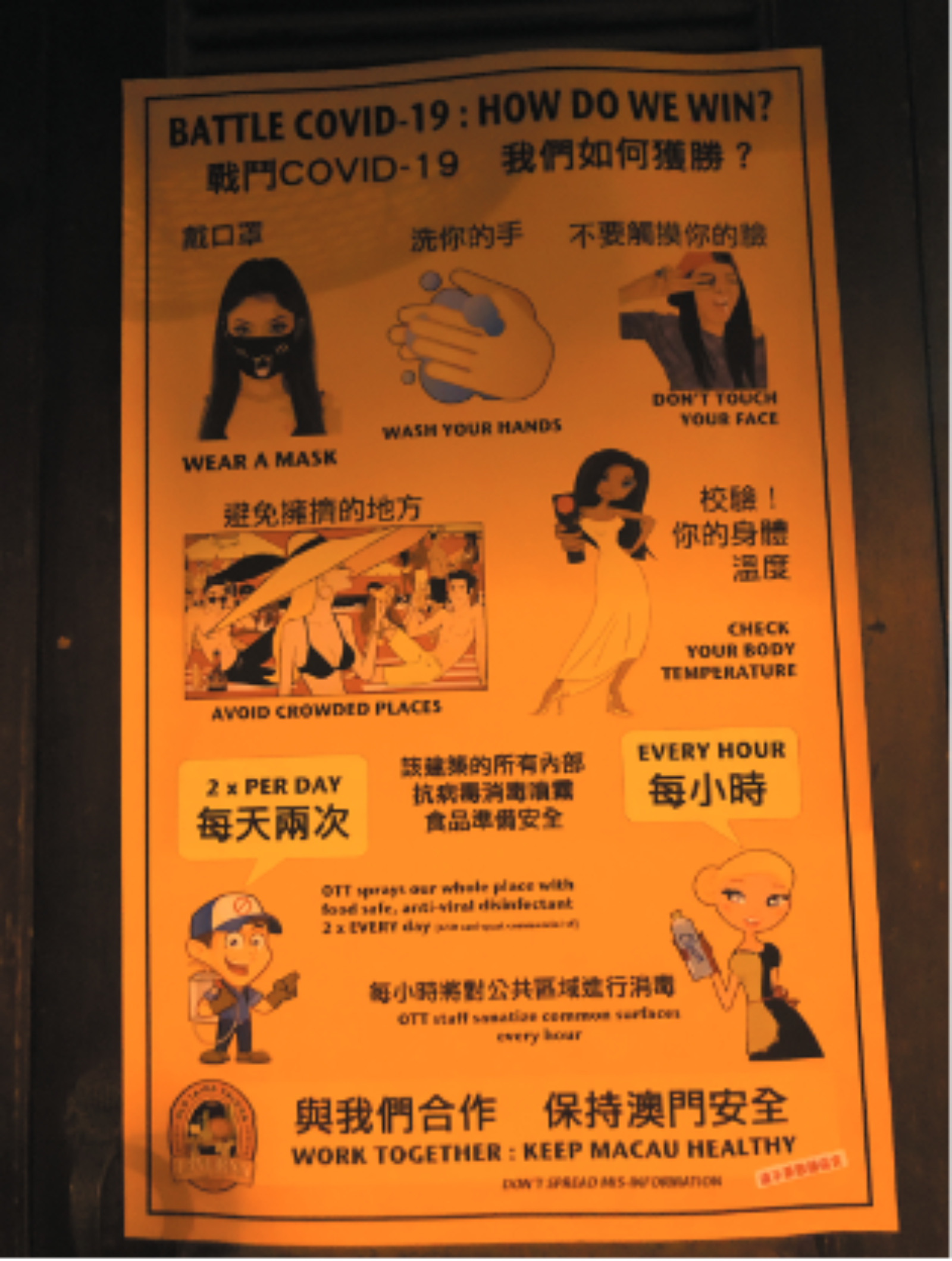

The authors document anxious immobility in its material, personal, and political aspects. Lockdown measures, such as a two-week complete closure of casinos followed by social distancing requirements thereafter and suspension of cross-border transportation, represented immobility in material form. Residents abided by new hygiene practices including minimizing physical contact by waving or bumping elbows and regular hand washing, which demonstrated the emergence of cleanliness “as a measure of a civilized, socially responsible, and mobile citizen in the state of potential contagion” (Zuev and Hannam 41). Although people cooperated with lockdown measures, they soon faced disruptions in their daily routines due to working from home, which dissolved the divide between personal and work time, and many found themselves becoming “nocturnal,” or sleeping more often during the day. Occupations that relied on residents’ mobility were disproportionately impacted, such as taxi drivers.

Anxieties around immobility worsened within a deserted urban environment that the authors describe as “uncanny and ‘indefinable’” (Zuev and Hannam 44), with constant announcements reminding citizens of lockdown measures. The accessibility and accuracy of technologies that track real-time pandemic statistics also created anxiety to reinforce immobility, as the authors recount a personal experience where a friend dissuaded them from visiting Hong Kong by showing them the real-time COVID-19 death toll in Hong Kong.

Immobility carried the political significance of exacerbating inequality between Macau permanent residents and non-resident workers. Low-income migrant workers were forced to stay in overpopulated rooms in Macau during lockdown to avoid losing their jobs and were unable to benefit from government consumption bonuses. Even non-resident professionals felt trapped and insecure, as one expressed, “But if you are not a permanent resident (and most of the foreign workers aren’t) even if you are top executive in a casino you cannot leave Macau as there is no knowledge when the border will be open again” (Zuev and Hannam 44).

The COVID-19 pandemic saw many countries impose quarantine restrictions on travelers or close their borders entirely, which disrupted the globalized economy and the flow of people and goods around the world. Lockdowns restricted people’s freedom of movement that many had taken for granted, making adapting to life during the pandemic even more difficult. Thus, the concept of anxious immobilities provides a lens that focuses on the inhibition of individual and mass movement that characterized much of the pandemic, as well as the resulting emotional challenges people experienced and its political implications. It particularly reflects the unique context of Macau, which relies heavily on cross-border mobility to and from mainland China and Hong Kong to support its tourism industry and the daily lives of its citizens.

Image Captions:

Figure 3. Poster encouraging hygiene. Source: authors. Via “Anxious Immobilities: An Ethnography of Coping with Contagion (Covid-19) in Macau” by Dennis Zuev and Kevin Hannam. Mobilities, vol. 16, no. 1, 14 Oct. 2020, pp. 35–50, bit.ly/430EJg8.Citation: Zuev, Dennis, and Kevin Hannam. “Anxious Immobilities: An Ethnography of Coping with Contagion (Covid-19) in Macau.” Mobilities, vol. 16, no. 1, 14 Oct. 2020, pp. 35–50. bit.ly/430EJg8, NON-FICTION, SCHOLARLY ARTICLE | CHINA. ll

Source Type: Scholarship on COVID-19 Studies

Country: China

Date: 14-Oct-2020

Keywords: Anxiety, Border Closures, Ethnography, Immobility, Impacts of Lockdown, Macau, and Pandemic Regulations